A Time For Equality: Managing the COVID19 crisis and building its aftermath

Rachel Mullen considers how responses to the Covid-19 pandemic reflect a very different type of politics

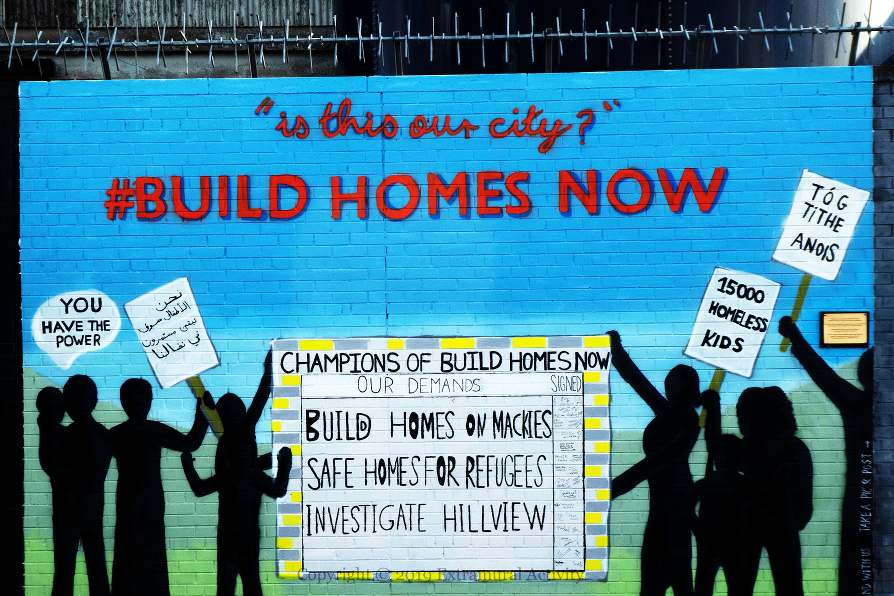

We have become too accustomed to a low energy politics on the island of Ireland: where progressive change is at best incremental or, at worst, impossible to achieve. Substantive change for equality, sustainability and human rights is thwarted and blocked by vested interests. It is weighed down and stymied by bureaucracy.

The response to the Covid-19 pandemic reflects a very different type of politics. Substantive progressive change is suddenly immediately possible.

In the Republic, over a period of days, social welfare policy was reframed. A wage subsidy was introduced to keep people in employment. An enhanced unemployment benefit was created for those who become unemployed. In the area of housing, a temporary prohibition on evictions and a rent freeze in the private rented sector were introduced: less than a few months ago such action was deemed to be unconstitutional by the dominant political parties. Most dramatic of all, our two-tier health system, an institutional expression of class-based inequality, has been temporarily eliminated.

Up to this point we had become used to, even accepting of, equality as an add-on to the ‘normal’ thrust of politics and policy. Equality has never been an imperative at the heart of political decision-making. We celebrate the equality crumbs from the table, only on offer in the good times and quickly withdrawn as the economy demands. These recent policy developments suddenly place equality to the fore as a key part of the solution to the current crisis.

We could be positive in seeing this current concern for equality as a recognition and expression of shared humanity and the importance of mutual support in the face of common threat. We might be cynical in seeing it as a product of the fears of the privileged: the pandemic can be spread by rich and poor alike; or the hardships resulting from the pandemic could be a source of instability and unrest. However, for whatever reason, it is clear that the crisis cannot be managed without some priority given to equality policies and initiatives.

There is an emphasis on solidarity in responding to people on the basis of need rather than ability to pay, or some measure of ‘most deserving’.

Public and political discourse now reflects a commitment to a human worth that is universal and involves an empowering focus on all of us as central to the solution to the crisis we face. This discourse and recent policy changes also have at their heart a concern for community, in expressing care for each other, and in ensuring access to necessary supports and services. There is an emphasis on solidarity in responding to people on the basis of need rather than ability to pay, or some measure of ‘most deserving’.

The media and political discourse, that has accompanied these policy changes, is underpinned by a value base that motivates us to think beyond self-interest, to a concern for the welfare of others. The sustained public engagement of the values of care, community, and solidarity is new. It replaces what to-date has been a sustained public engagement of oppositional values that motivate a ‘what’s in it for me’ self-interest: the values of individualism and competition that underpin the neoliberal economic model that has dominated for decades.

While values, of care, community, and solidarity might be new in their prominence, they are not new in society. European and world values surveys have consistently demonstrated that the majority of people, including in Ireland, prioritise pro-social values over pro-self-interest values as being of greater personal importance. Yet, the pervasive engagement of neoliberal values of self-interest, in the media, through consumer advertising, and in political and policy discourse has strengthened self-interest values. This results in a diminished engagement of pro-social values, to such an extent that, as one 2016 UK-based study demonstrated, people erroneously believe that they are alone in being motivated by pro-social values.

The response to the Covid-19 pandemic, however, has upended this pervasive engagement of self-interest values. The swift policy changes give expression to the common good. The pro-social values of community, care, and solidarity, currently being amplified in media and political messaging, underpin this focus on the common good in what may arguably be the most seismic values shift in the Republic in decades. The research tells us that values are akin to muscles: the more they are engaged, the stronger they become. A more egalitarian society would be motivated through this strengthening of community, care, and solidarity values, if their engagement can be sustained.

We need to learn from, and build on this moment. Civil society needs to work together to sustain the public engagement of pro-social values: this will be key to a sustained mobilization of public support to ensure equality measures taken now, are not reversed once the crisis has abated, and that further progressive change can be achieved. Civil society needs to work together in devising and advancing shared agendas, based on these values, for a more just, equal and sustainable Ireland.