The Proof Will Be in the Pudding: PPR's Response to NIHE Homelessness Policy Consultations (part 2 of 2)

The Housing Executive's draft Ending Homelessness Together Strategy 2022-27 and Homeless to Home draft strategic action plan for temporary accommodation have clear positive elements -- but how will they impact the most marginalised of this marginalised group?

This is the second of a 2-part response to Housing Executive consultations on new draft policies around homelessness and temporary accommodation. The first part reviewed some positive content in the draft policies, but also highlighted a vitally important group – homeless children – that they largely overlooked. Part 2 looks at another under-acknowledged and under-served group: people who are homeless but who do not have FDA status.

Homeless people without FDA status

Another area of great concern is the cohort of homeless people who do not have official FDA status. One such group is made up of homeless people who have applied but been denied FDA status. In 2020/21, only 9,889 of the 15,991 households (62%) that presented as homeless were accepted. A few others were apparently tallied as repeat cases. The remainder were “not owed a full housing duty” as they failed to meet at least one of the four statutory criteria (eligibility, homelessness, priority need and intentionality).

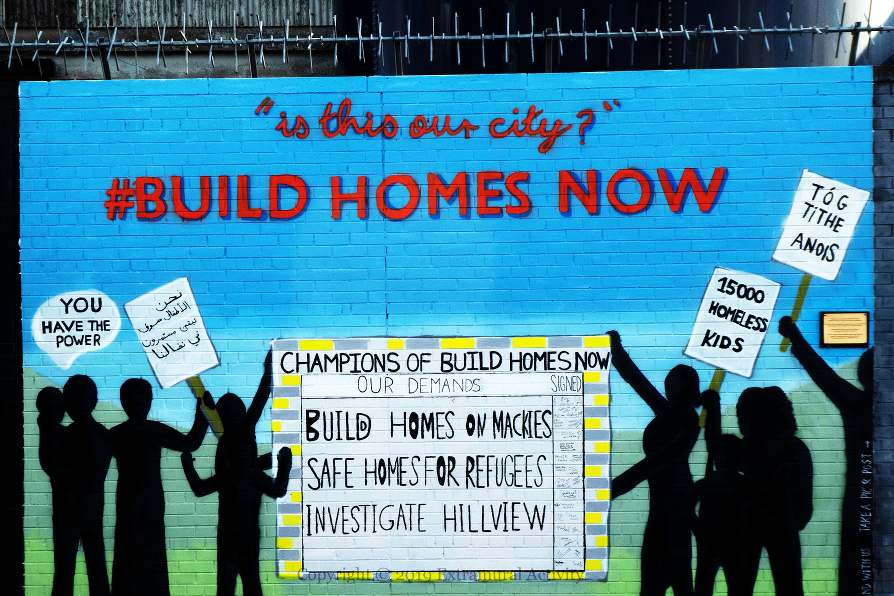

Pre-pandemic, PPR supported the Homeless not Voiceless group of people who had been denied Full Duty Applicant status – often for reasons that were not clear to them, their peers, support workers, PPR or anyone other than the Housing Executive staff who made the call. The draft homelessness strategy says that it “ensures the provision of appropriate support services” to this group, but there is no real detail about what this means, or which if any of the proposals made in the draft policies apply to them.

Equally of concern are homeless people who have not even applied for FDA status. The Housing Executive-commissioned research paper underpinning the strategy noted “a perception amongst some young single people (particularly males) that there is little point in applying to the Housing Executive for accommodation as they will be deemed to have no priority need” (3.18). The draft policy refers to partner organisations potentially identifying such cases of ‘hidden homelessness’, but again offers little substance.

For both of these groups, what is missing is a frank and participatory interrogation of the current criteria, how they are applied, who they are excluding, why and what to do about it. This effort to remove barriers to homeless people accessing support has taken place to an extent in Scotland; as a result, since end 2019 local authorities are no longer required to investigate whether an applicant is ‘intentionally’ homeless. ‘Intentionality’ remains a criterion here, however; the same exercise is clearly needed, but at the minute it’s the elephant in the room.

Finally, another key group in this area is made up of foreign nationals deemed to have ‘No Recourse to Public Funds’, including (often temporarily) refused asylum seekers as highlighted in various reports from groups supported by PPR. Pre-Covid, people with an NRPF designation were only explicitly entitled to advice about homelessness; but under the UK-wide ‘Everyone In’ public health initiative for rough sleepers, a Memorandum of Understanding was set up between the Housing Executive, the Department for Communities and the Department of Health to provide emergency shelter for them during the pandemic. Around 60 people were reportedly provided with housing under the scheme, however PPR and other organisations working with this community have witnessed the extent to which they face barriers accessing this support – including overly restrictive interpretations of eligibility.

This agreement runs until at least the end of March 2022. The draft strategy includes an aim to explore alternative routes with the Department for Communities and the Department of Health through which to provide accommodation and support to people with no recourse to public funds when the current arrangements as part of the COVID-19 response end.

The Housing Executive and departments have the chance to embed a pandemic-era policy in the interest of a more humane future. There are opportunities to learn from approaches taken in Scotland in this regard, but as yet, seemingly little co-ordination or forward thinking. This area will be another telling indicator of how deep the new person-centred, responsive approach runs in the Housing Executive going forward.