Social Housing Development in Northern Ireland: Who's Counting?

Question: What do you get when you compare data published by NI's official statistical agency against Housing Executive figures? Answer: More questions.

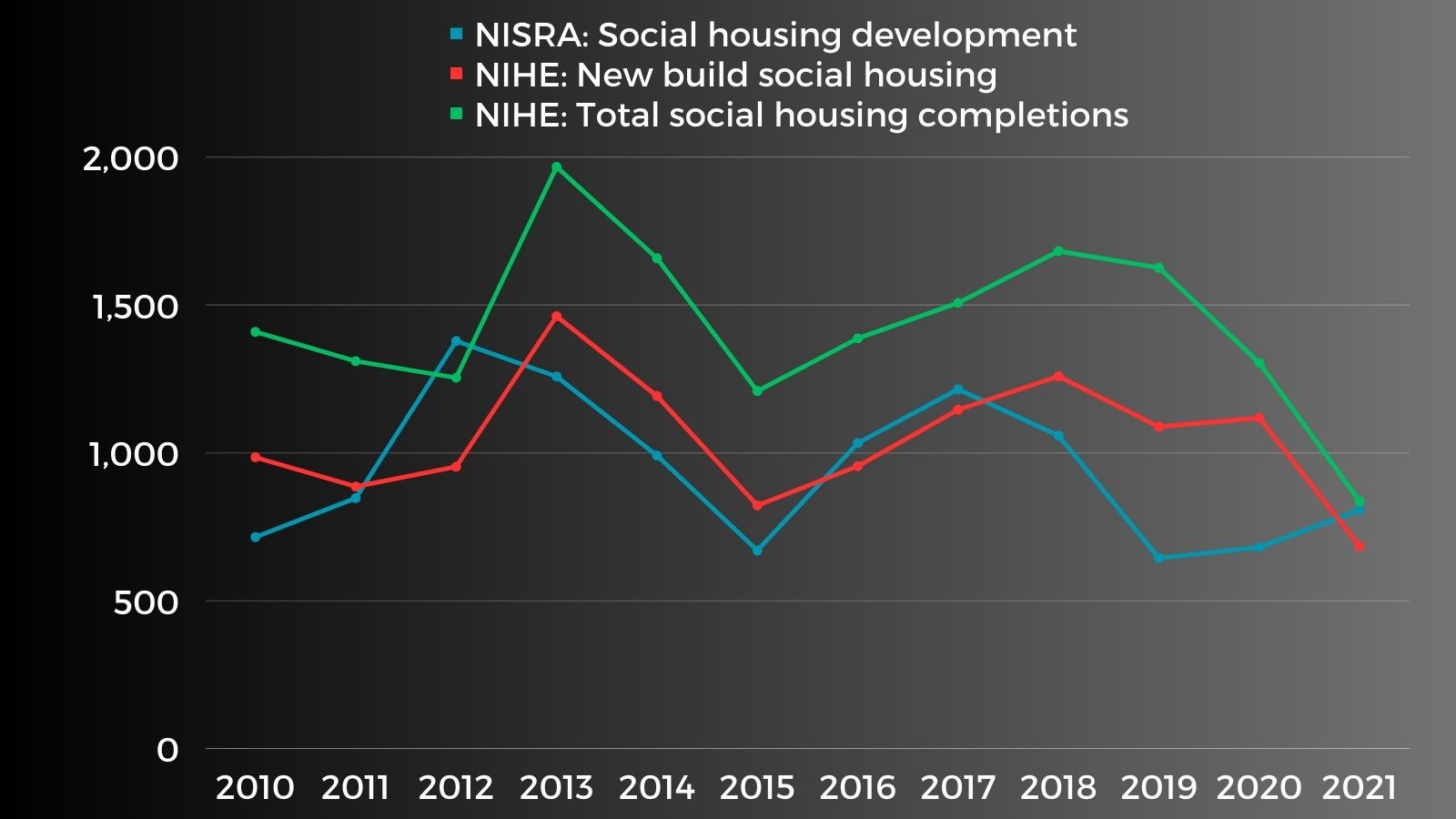

In its analysis and reporting of social housing need, PPR rely upon data from the relevant body, the Northern Ireland Housing Executive. In trying to chart growing housing need against new social housing earlier this year, though, PPR turned initially to a what seemed an authoritative, uncontroversial and handy data set published by NISRA on 16 November 2022, in the ‘Housing’ section of its NI: In Profile resource pack. Basic analysis of that information indicated that on average 941 new social homes had been built each year between 2010 and 2021.

In recent months, Housing Executive personnel noted and queried PPR’s use of that statistic. We explained where we’d found it and asked, in the event that Housing Executive data was different, that they help us understand any discrepancy.

NIHE figures for new build social housing, when they came, were in fact significantly different from the NISRA ones (which it turned out were based on Building Control reporting, via the Department of Finance). NIHE pointed out that the timescale of this reporting would be different; and also that Building Control may at times be unaware of instances in which private developers build what end up as social homes; all the same, the differences were staggering. NIHE data showed an average of 1,046 new build social homes completed each year between 2010 and 2021 – 11% higher than the average of the NISRA figures. Even more significantly, NIHE’s total social housing ‘completions’ (which include, in addition to new build social homes, a range of other categories) amounted to on average 1,429 homes per year over the same time period – half again the average given by the NISRA figures.

Image caption: NISRA and NIHE datasets relating to yearly social housing provision

The NIHE ‘social housing completions’ data includes – on top of newly built social homes – those acquired ‘off the shelf’ or as ‘existing satisfactory purchases’, as well as homes where ‘rehabilitation’ or ‘re-improvement’ works were completed. When, in May of this year, a range of media outlets reported that Northern Ireland had ‘smashed its delivery targets’ by completing 1,449 social homes, the articles didn’t clarify how many of those completed works were to already-existing social homes (potentially, according to the FOI figures, over 100), or what the figures meant in terms of overall net social housing gain for the year – not the fault of journalists, but just because that information wasn’t available. And in the face of over 45,100 NI households on the waiting list – more than half of them officially recognised as homeless – maybe those details don’t matter.

Then again – with the social housing budget facing cuts despite the ever-rising number of people living with acute unmet housing need – maybe absolute clarity about the figures and what they represent does matter, now more than ever.

This confusion over how many new social homes there are at the end of any given year’s work isn’t the only murky area we’ve come across while trying to understand how our housing system works. Another example: the Housing Executive’s Social Housing Development Programme table of new social housing schemes lists new developments by Local Government District and Parliamentary Constituency – sensible on the face of it, except for the fact that the numbers of households on the waiting list, in housing stress and with FDA homeless status are tracked under wholly different, apparently unmatching geographical categories (eg Common Landlord Area, Housing Need Area).

The lack of ground for comparing the two data sets, need and provision, raises the question of how much weight is actually given to levels of local housing need in decision making around what social housing schemes are built, and where.

This means that any progress in building new social homes in a given area can’t be set – at least by the general public – against the number of local families in need. The degree to which social homes are or aren’t provided in the areas where they are most needed also can’t be easily tracked. The lack of ground for comparing the two data sets, need and provision, raises the question of how much weight is actually given to levels of local housing need in decision making around what social housing schemes are built, and where. Surely it would make sense for housing need data to match up with housing provision data, and vice versa?

Belfast’s new Local Development Plan strategy, and in particular its HOU5 policy (which mandates that 20% of all new residential developments of five or more units include 20% ‘affordable’ (ie, social, co-owned or intermediate) housing) make transparency all the more essential. Belfast City Council and developers - with input from the Housing Executive - will be deciding what type of new builds meet the new ‘affordable housing’ requirement, wherever they happen to be building. With so many households struggling to find or keep a home, and with housing-related stress impacting every aspect of so many lives, the promise of more ‘affordable’ homes is a lifeline. Whether that promise lives up to its potential is of tremendous public importance – but how will we know?